Gunpowder, grass, jasmine, pine, pollution, and patchouli are some of the odors wafting around galleries, museums, and studios these days as artists incorporate scent into the esthetic experience

Gunpowder, grass, jasmine, pine, pollution, and patchouli are some of the odors wafting around galleries, museums, and studios these days as artists incorporate scent into the esthetic experienceA visitor stepping into Koo Jeong A's installation for the Dia Art Foundation at the Hispanic Society of America may be overwhelmed by an unexpected assault on the senses. Like a cedar closet, the almost empty gallery has its own distinct aroma, in this case an olfactory artwork, entitled Before the Rain, which is meant to capture the atmosphere of an Asian city on a steamy day. Over a three-month period, the Korean artist worked with perfumer Bruno Jovanovic of International Flavors & Fragrances, a leading company in the design of synthetic scents, who distilled her memories and impressions into an amalgam of smells—dry woods, minerals, fern, musk, tars, and lichens—to summon the sensation the artist remembered.

"I was compelled to create a scent that evokes the almost violent atmospheric tension that exists before a thunderous rainstorm," says Jovanovic, who views the piece as a true collaboration. "The whole work was about dissecting the entire experience and then re-creating it in a nebulous form."

The philosopher Immanuel Kant believed that the sense of sight is superior to all the other senses. A number of artists today, like Koo Jeong A, would disagree with him. They are incorporating the sense of smell into the esthetic experience. Smoke and pollution, as well as patchouli and pine, have become part of their palettes. Although scent is a fragile and ephemeral medium, it is making an impact in museum shows and at symposia as a new trend in art.

"Working with the sense of smell is probably the hardest material, because it is very subjective and it changes from person to person," says Yasmil Raymond, curator at Dia, who oversaw the development of Before the Rain. "Koo Jeong A had a very specific concept about this smell, but she had to find a way of articulating through language what that was to a perfumer, who conceived the chemical composition. It was really the hardest thing I had ever done as a curator."

Contrasting this collaboration with the more traditional artist-fabricator relationship, Raymond explains, "Usually you are working with things you can see and touch. In this case, we were working solely with language, and a very subjective language at that."

A number of other recent projects have asked museum and gallery visitors to use their noses as well as their eyes. Shown two years ago at the New Museum in New York, Haegue Yang's Series of Vulnerable Arrangements—Voice and Wind incorporates Venetian blinds, electric fans, and scent atomizers to create the sensation of entering various unspecified locations. Made originally for the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2009, the installation offers an intimate and subjective experience, with each visitor free to interpret the odors.

Smell You Later!

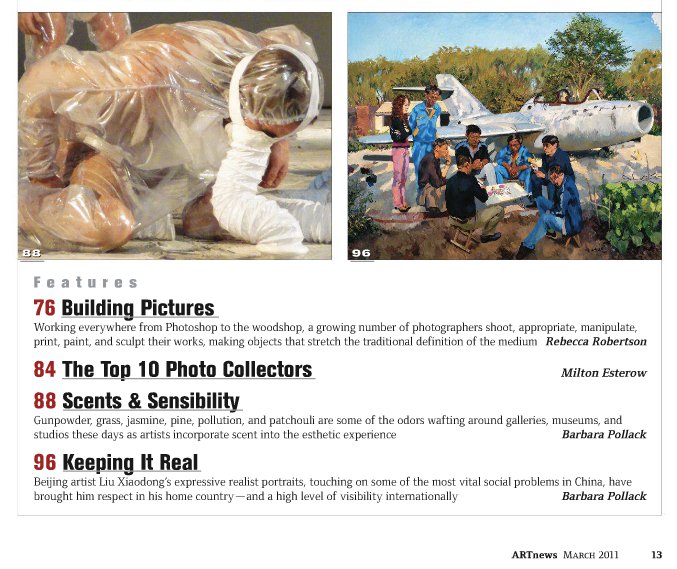

Peter De Cupere collected the sweat of dancers wearing plastic suits duiring a 15-minute performance choreographed by Jan Fabre. He applied the concentreated essence, enclosed in a glass box, to a wall at the dance company’s home base, in Antwerp. Visitors can smell it through a hole in the glass.

De Cupere is one of a growing number of artists around the world who are incorporating scent into the esthetic experience. Smoke and pollution, as well as patchouli and pine, have become part of their palettes….

Belgian artist Peter De Cupere exhibited his Olfactory Tree, a latex sculpture of a life-size tree trunk embedded with scents of the forest, at the Pocketroom art space in Antwerp, while Japanese artist Maki Ueda presented her Olfactoscape, an aromatic journey evoking a landscape of cherry blossoms and fields of grass, in a small empty room at the Dutch consulate in Osaka.

Czech artist and architect Federico Díaz had a surprise hit at EXPO 2010 in Shanghai last year with his installation LacrimAu, which featured a golden teardrop about 30 inches high, housed in a glass cube. One person at a time could enter the cube, sit down, and don a headband with sensors that read his or her brain waves and translated them into a personalized scent.

New York artist Kiki Smith has created her own fragrance, Kiki, in collaboration with the French fragrance designer Christophe Laudamiel. The limited edition of 4,000 sells for $175 a bottle.

In September the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam held a one-day symposium, called "do it—smell it," on olfactory developments in contemporary art, with contributions from Caro Verbeek, an art historian specializing in art and the senses, and Jim Drobnick, an authority in the field of smell and contemporary culture and author of The Smell Culture Reader.

Simultaneously, museums have begun to turn their attention to the perfume industry, for the first time examining perfumes as works of art on a par with couturier gowns and other museum-worthy design objects. In March 2010, Parsons The New School for Design and the Museum of Modern Art, in partnership with International Flavors & Fragrances, Coty Inc., and Seed, a science magazine, presented a symposium, "Headspace: On Scent as Design," which brought together such diverse participants in this field as scent artist Sissel Tolaas, neurobiologist Leslie Vosshall, and architect Toshiko Mori, as well as perfume designers.

In December the Museum of Arts and Design in New York announced that it was establishing the Center of Olfactory Art, appointing former New York Times scent critic Chandler Burr as its director. Burr will also organize "The Art of Scent, 1889–2011," the first museum exhibition devoted to perfume as art, which will open this fall.

"We are establishing the idea that olfactory art is as important as any other aspect of design," says museum director Holly Hotchner. "Scent is a really important part of people's lives and obviously a multibillion dollar industry, yet 99 percent of the population never thinks about how it is designed."

"I hate the word 'perfume,'" Burr says. "It's somewhat better in French: 'parfum.' Perfume in Anglo-Saxon culture means something that is generally very much feminine—powdery, sweet stuff. It is not a word that we use well. Americans use the word 'cologne' to denote the masculine. It's gendered." But Burr's focus for his upcoming exhibition will be on designer fragrances.

"Most people don't understand that when Alberto Morillas makes a perfume called "Pleasures" and it comes out under the brand of Estée Lauder, and they have Elizabeth Hurley or Gwyneth Paltrow in the ad, and it is sold, that it is a commercial product that is also a work of art," he says. "What interests me is helping people understand that these are actually works of art, that they are beautiful and esthetically important and meet all the criteria for art, equal in terms to painting, sculpture, music, architecture, and film."

In contrast, Verbeek is not looking at the fragrance industry but at the history of art in the 20th century to find artworks that include an olfactory component. Her master's thesis, completed at the University of Amsterdam in 2002, was inspired by Ernesto Neto's We Fishing the Time (densidades e buracos de mihoca), 1999, at the 2001 Venice Biennale. "I smelled it way before I saw it, and I had no idea that this was part of a work of art, so once I was in the room, I was really surprised," she recalls. "I thought, I am an art historian, but I don't know how to deal with this. I don't know how to understand this. I have no frame for this."

Verbeek has identified many 20th-century works with an olfactory component. Marcel Duchamp, for example, filled a room with burnt coffee at an early Surrealism exhibition in Paris. The Stedelijk Museum owns Ed Kienholz's The Beanery (1965), which smells of alcohol, smoke, and even the artist's own urine to evoke the feeling of being in a bar.

"In the 1960s, when performance art and installation art emerged, this gave a chance to a lot of artists to use more senses, and in the 1990s you see technological developments, like synthetic smells," Verbeek says, citing as a breakthrough the Canadian artist Clara Ursitti's collaborations with scent expert George Dodd, whose London-based company, Kiotech International, developed a diagnostic "nose," a machine that could measure aromatic molecules, in 1998.

"Smell is one of our senses and an incredibly important one, so it is silly that artists haven't used it for a longer time or that art historians haven't paid more attention to it," says Verbeek, who is currently working with artists Sue Corke and Hagen Betzwieser on a "postcard from the moon." It contains the scent of the moon's surface, which, according to astronauts the pair interviewed at NASA, smells of gunpowder and heavy metals. The moon scent, developed by flavorist Steve Pearce, will be distributed by the Stedelijk later this year. "Smell has a big effect on visitors to the museum, because smell is linked to memory. Smell enhances the sense of reality, and smell enhances emotions," says Verbeek.

The fact that smell can reach audiences beyond the museum has attracted the interest of several artists. In 2000 New York artist Gayil Nalls created the World Sensorium, a scent sculpture blended from iconic aromas from every country in the world—eucalyptus from Australia, jasmine from China, tobacco from Cuba, and pine from the United States—and distributed on printed cards that were showered down on Times Square revelers at midnight on the night of the millennium.

According to Nalls, the experience of growing up in 1960s Washington, D.C., a city of monuments and mass demonstrations, was behind her wish to create a more universal experience, less culturally bounded than the statues and events that colored her childhood. She was also inspired by Joseph Beuys's 1980 Cooper Union lectures about "social sculpture." To make her own social sculpture, she spent years asking officials from around the world to choose a scent to represent their countries, an effort supported by UNESCO. She then mixed the world fragrance herself, in her laboratory-like studio, based on the populations of the various countries.

Chrysanne Stathacos has reached over 50,000 participants with The Wish Machine, a project that makes use of refabricated vending machines to distribute vials of essential oils associated with basic hopes and desires: lavender for happiness, clove for lust, mint for communication, basil for money, hyacinth for peace, and rosemary for home. Stathacos's machines were inspired by wishing trees in India (trees on which people hang offerings in hope of having wishes fulfilled) and originally commissioned by Creative Time in 1997 for Grand Central Station. She has since brought them to public venues in India, Germany, Canada, Switzerland, and throughout the United States.

"People can stop and smell and maybe dream for a second or have a brief moment outside the busy city," Stathacos says of the piece. "It becomes this effect of going to another place, maybe a memory of a garden or of someone bringing you flowers, maybe a memory of healing." For this reason, The Wish Machine has often been included in exhibitions on AIDS and recovery.

"What is so wonderful about this kind of project is that it is so ephemeral; it really defies market pressures," says Stathacos, who usually shows her work at kunsthalles and alternative art spaces. Her point of view is shared by most of the artists working in the medium of scent, who rarely have gallery representation. De Cupere, whose Olfactory Tree was shown at a noncommercial art space and is priced at €40,000, usually works on commission. A recent project involved collecting sweat from dancers performing with the choreographer Jan Fabre and distilling it, then applying it to a wall of the company's home base in Antwerp. Visitors can smell it through a small hole in a glass box cover.

Nalls's World Sensorium is part of the exhibition "Objects of Devotion and Desire" at the Bertha & Karl Leubsdorf Art Gallery at Hunter College (through April 30). The first edition of 18 bottles sells for $3,500 a bottle.

Nalls objects strongly to the use of synthetic scents. She, like many other olfactory artists, uses only natural fragrances and essential oils. "I call it 'rewilding the mind,'" she says, hoping that her projects will familiarize people who are used to "grape" chewing gum and "alpine-scented" candles with what the world really smells like.

New York activist-artist Lisa Kirk was seeking to evoke a social experience when she developed a perfume called "Revolution" for her 2008 exhibition at Participant Inc. on the Lower East Side. Kirk contacted witnesses to political upheavals, including Central American revolutionaries and ex-Black Panthers, and asked them, "What does revolution smell like?" The answer: dried blood, smoke, burning tires, gasoline, and urine. Kirk relied on perfumer Patricia Choux to create the scent and jeweler Jelena Berhrend to design containers that looked like pipe bombs, fabricated in silver, gold, and platinum, and priced from $3,750 to $47,750 per bottle.

"If we can't start a revolution, at least we can create a fragrance that symbolizes rebellion," says Kirk. The project was shown in 2008 at MoMA PS1, complete with an installation of a laboratory, hanging upside down, from the ceiling. Since then, with the assistance of scent designer Ulrich Lang, Kirk has brought out a less expensive variation of "Revolution" that has been marketed throughout Europe.

Lang has worked on many collaborations with artists, using Antwerp-based art dealer Roger Szmulewicz to market his fragrance, "Anvers," and commissioning Erik Swain, Katy Grannan, and Matt Licari to design the packaging. In 2005 he also worked with Daniel Bozhkov (represented by Andrew Kreps Gallery in New York) on the fragrance "Eau d'Ernest" for the Istanbul Biennial.

"Using the form of fragrance to express an idea is a challenge," says Lia Gangitano, director of Participant Inc., who has worked on several scent-based projects and finds in them the potential to make something transgressive. She cites as an example the New York collaborative Lovett/Codagnone's 2003 installation and performance ASK*, at the Laura Mars Group in Berlin and TRANS>area in New York. The team infused a room with the smells of aphrodisiacs and body odors while they read passages from Dominique Laporte's History of Shit and the screenplay for Pier Paolo Pasolini's Salo (120 Days of Sodom).

Currently Gangitano is developing a "trans fragrance" with Justin Bond, the Radical Faerie performance artist best known as Kiki, of Kiki and Herb, to accompany Bond's upcoming exhibition of paintings this fall. "He is looking for something less binary than the usual unisex perfume," says the curator. "Right now I do think there are issues at play in contemporary art that involve immediacy and intimacy—and what could be more so than putting a scent on your body."

"I think what these artists are after is not making a sculpture but making an environment," says Yasmil Raymond, summing up her experience with olfactory art. "The work, when it smells, enters the realm of a human being, the living. This life component enters into it—which is very different from looking at a Monet."

Barbara Pollack is a contributing editor of ARTnews.

Article from ARTnews

Read also:

http://artnewsmag.tumblr.com/post/3727734210/smell-you-later-peter-de-cupere-collected-the

| < Prev | Next > |

|---|